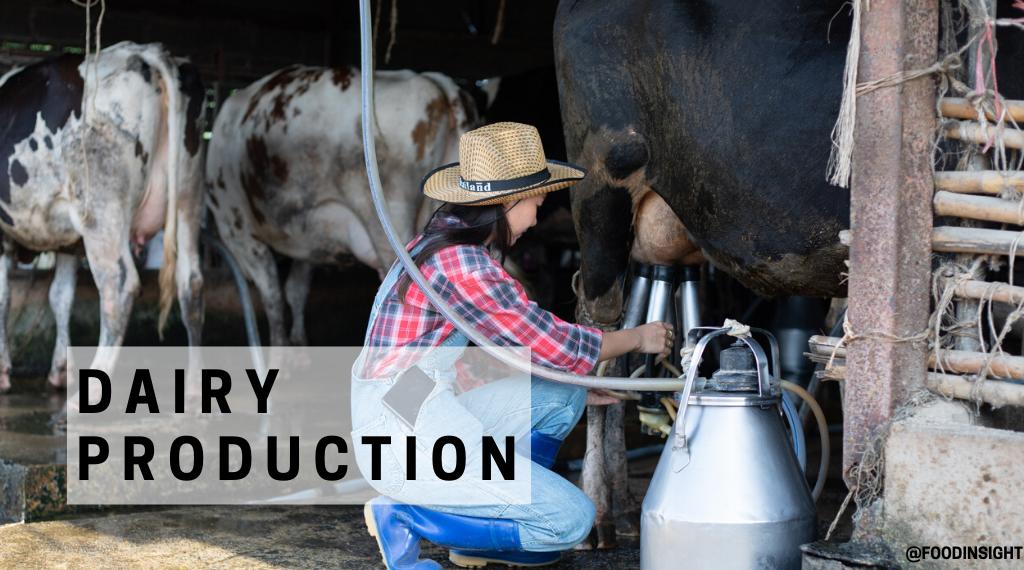

Dairy is often something I rely on—ice cream and froyo keep me cool in the summer, hot chocolate and lattes keep me warm in the winter, and a cold glass of milk can instantly transport me back to childhood. All thanks go straight to the dairy cows and farmers working around the clock. In fact, a single cow can produce approximately 6.5 gallons of milk daily and supply over 21,000 pounds of milk yearly, not counting the milk her newborn calf will drink. That milk is just the start for dairy lovers. It may be transformed into cheese, yogurt, or a number of other food products through a series of well-monitored, science-driven steps on the farm, in warehouses and in factories.

From cow to carton

Shortly after giving birth to a calf, a dairy cow will start producing milk, and she will continue to do so for about ten months. This milk is collected on the farm and then transported for further processing, specifically for pasteurization and homogenization. Pasteurization is the means of treating a food product, often by heat, to reduce the risk of foodborne pathogens surviving in the product that could potentially make consumers sick. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates this process very carefully for milk products, specifying the amount of time and temperature milk must be heated—for example, lower temperatures require longer time to make sure any harmful pathogens are destroyed. The next step, homogenization, ensures that the contents of milk—its protein, fat and sugars—remain one consistent mixture rather than clumps separated among liquid. The pasteurized, homogenized milk then may be packed into various containers, stored at safe temperatures, and shipped to grocery stores and markets for human consumption.

Plant-based products like almond milk and oat milk will similarly go through an FDA-mandated process to ensure their safety for human consumption, but they aren’t nutritionally or structurally equivalent to cow’s milk. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, since one product comes from an animal and the other from a plant. Typically, plant-based milk products have less protein than cow’s milk, which not only affects their nutrition but also may impact how they act as ingredients in cooked items like sauces and baked goods. Another key difference, and one reason someone may reach for almond milk over some brands of cow’s milk, is that non-dairy alternatives do not contain lactose, a sugar unique to cow’s milk that may cause digestive issues in lactose-intolerant individuals. However, there are many brands of cow’s milk that also offer lactose-free options.

It’s all Greek to me

If it isn’t packaged into a translucent bottle or carton, milk might be further processed into yogurt or cheese. Yogurt production begins with the addition of live lactic acid-producing bacteria, such as Lactobacillus bulgaricus, to pasteurized milk. The milk-bacteria mixture is then left for several hours at a heat high enough to allow the bacteria to grow but low enough so that they don’t die—typically 105–115 degrees Fahrenheit. During this time, the bacteria change the acidity and texture of the yogurt, creating a firmer product. While all yogurts will undergo the processes of pasteurization and incubation, they don’t all turn out the same. Widely popular Greek yogurt is typically thicker in texture, higher in protein, and lower in carbohydrate than standard yogurt. This difference is due to the fact that Greek yogurt is strained one or two more times than regular yogurt. This extra straining removes additional liquid, called whey, which contains lactose and some vitamins and minerals. Since more whey is removed, Greek yogurt ends up being a lower-lactose product that may be gentler on lactose-sensitive individuals’ stomachs.

Time to get cheesy

Adding live bacteria to milk doesn’t always end in yogurt—it may result in the production of cheese. Milk that has been acidified, either by means of adding acid-producing bacteria or an acid-like vinegar or citric acid, can become cheese through a series of careful steps. Once it reaches a certain level of acidity, an enzyme called rennet is added so that the milk proteins can join together and form a semi-solid gel. This is called the curd, which is then broken up into smaller pieces depending on how dry the final cheese will be. The smaller the pieces, the less moisture they retain and the drier the end product. Cheesemakers are essentially done at this stage if they plan to make cottage cheese. To finish up cottage cheese production, some of the liquid (whey) is strained from the soft curds, and a creaming agent, often milk cream, is added.

However, for a wheel, slice, or block of cheese, the curds need to finish drying and aging. Typically, the curds are pressed, washed, and drained to remove the whey. Some cheeses may have more ingredients, such as salt, added at this stage to add both flavor and structural development. After a defined period of aging, the cheese then may be packaged for consumption. Longer aging will result in sharper cheeses, which often have tangier, more complex flavors.

How it’s all regulated

Dairy products and their plant-based counterparts are all regulated by the Food and Drug Administration. The steps during processing are often similar for both dairy and non-dairy products to ensure proper food safety; almost all products undergo pasteurization to ensure the reduction of risk of foodborne illness. However, labeling under FDA guidelines can be a concern. Specifically, the FDA defines milk as a product that comes from “one or more healthy cows.” However, terms like almond milk and soy milk are widely used and are part of the common vernacular. While the majority of consumers understand that the plant-based products do not contain cow’s milk, this labeling may cause confusion among some individuals. Therefore, knowing how to read a label from front to back is essential to understanding what is contained in the food product you’re buying.

Until the cows come home

June is National Dairy Month and a natural time to celebrate all dairy has to offer, but dairy farming is a non-stop job. Farmers care for their cows 365 days a year to help deliver high-quality, safe, and nutritious milk, cheese, and yogurt to many tables. Next time you pick up a carton of ice cream or a slice of cheese, remembering the process from farm to factory to fridge may help you appreciate each bite just a bit more.

This article was written by Courtney Schupp, MPH, RD.