In July, Trends in Plant Science published an opinion piece on the psychology of opposition to biotechnology, entitled ‘Fatal Attraction: The Intuitive Appeal of GMO Opposition.’ The premise? We have strong scientific confidence in the fact that biotechnology is safe. Major authorities on food, health, and science—from the American Medical Association to the World Health Organization to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics—continue to review the vast body of evidence and confirm that biotechnology is safe. A meta-analysis of more than 1,700 separate studies determined that no credible studies showed any illness or health hazard from eating food produced using biotechnology.

It’s become pretty clear that the science isn’t the issue here. But nearly 70 percent of the conversations about biotechnology on social media are negative. So where is the gap coming from?

Stefaan Blancke and his team argue that some of the processes of human intuition make us “vulnerable to misrepresentations of GMOs.” What is going on with those intuitive processes, and how can science communicators navigate it to spread credible information?

We fill our mental cabinet with what we already know.

We fill our mental cabinet with what we already know.

The process of genetic engineering is something that most of us never learned in school, so it’s a tough prospect for us to mentally categorize “food biotechnology” in the 2.5 seconds it scrolls by in our newsfeed. The process isn’t simple to understand intuitively—it takes some legitimate time and energy to understand. Our brains go to things that we know, like that “chemicals” are scary. It’s the reason that Mom locked up the cleaning products under the sink, right?

That’s not at all what plant breeding of any sort looks like, but some minds are vulnerable to that suggestion because most of us have never seen (or even thought about!) different kinds of plant breeding.

We think we’re “better safe than sorry.”

We think we’re “better safe than sorry.”

No matter how small the likelihood of harm is, we’re hardwired to feel much more emotionally about that risk than potential benefits. David Ropeik explains, “even if a risk is small, the potential for harm (loss) carries greater emotional power, so fear overwhelms purely objective consideration of the factual evidence.“ Especially in a situation where we’re misapplying our experience (see #1), this impulse can really work against our ability to make smart decisions.

Our intuition is particularly vulnerable to this kind of fear about food. Blancke et al. explain that our human ancestors dealt with serious health threats from eating spoiled food, so it made more sense for them to “forego a nutritious meal because it is erroneously considered toxic or contaminated.” So, our intuition has a pretty strong hair-trigger in this area. It’s obviously just fine to be cautious and want to minimize risk- but it’s worth it to take the time to figure out what the real risks to our health are (food-borne illness anyone?). Which leads us to….

We think if it’s “just not natural,” it must be scary.

We think if it’s “just not natural,” it must be scary.

Ropeik has highlighted that “risk perception research has found that natural risks don’t feel as scary as the equivalent man-made risks.” You may remember our heart-attack-like expressions when Gwyneth Paltrow, professed lover of all things organic, said that she didn’t believe the sun could be bad for you, since it’s natural. It goes without saying (oh wait, it apparently does not) that this line of thinking is very, very dangerous and distracts us from “natural” risks like E.coli.

The impulse toward “natural,” especially around genetic engineering, matches closely with essentialism—the idea that everything has an unobservable, immutable core determining its identity. Does whether a technology is man-made have anything to do with whether it’s risky? No.

Blancke et al. highlighted how crazy imagery taps into this fear:

“Anti-GMO activists bombard the public with edited images that imply that GM food cannot be trusted, such as tomatoes with syringes or suspiciously blue biotech strawberries amid fresh red ones. Bt crops are described as poisonous and instigate the fear that biotech crops will ‘contaminate’ the surrounding environment. Moreover, disgust also affects our moral judgment.”

In fact, crops produced with biotechnology really just look like crops, and GE plant breeding actually targets far fewer genes (that “essence”) than traditional hybrid plant breeding or other methods used in organic production. Other ways that we, as humans, interact with our environment, from communications towers to medical treatment to the centuries of domesticated crops, have created incredible benefits, and biotechnology can and does do the same.

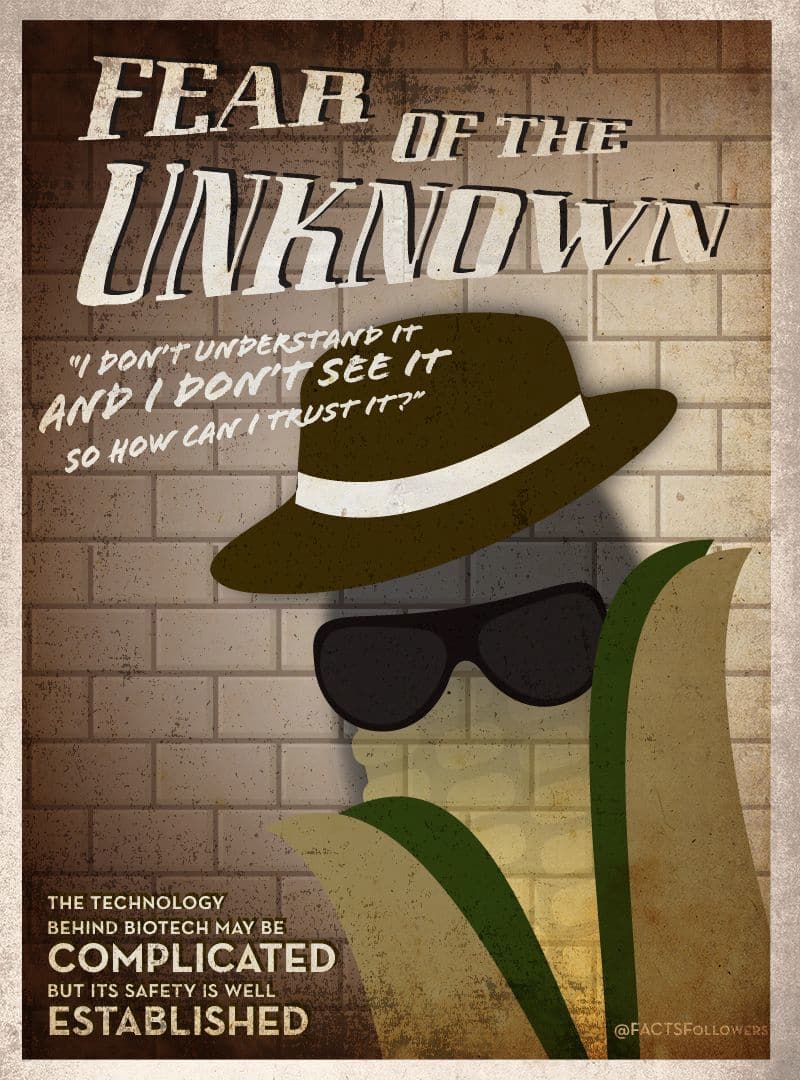

We are very, very uncomfortable with uncertainty.

So here we are—confused about what biotech even is, afraid of the “unnatural,” and at the height of our risk aversion. Especially without an understanding of all the research that’s been done (not to mention the extensive government approval process for any new varieties), it leads to the question: “Sure, I don’t know if there are dangers from biotechnology, but what if I find out about some in the future? Or what if there are some that researchers haven’t even discovered yet?”

Technically, that could be true with many well-tested technologies or products—organic and otherwise. There’s always some degree of uncertainty about what the future will hold. The science behind biotech may be complicated, but its safety is well-established.

If we decide that the large volume of science that exists isn’t enough, we may think we’re avoiding uncertainty. But we wouldn’t be. We fear risk, but there is a risk in allowing ourselves to be paralyzed by fear. Biotechnology is a tool that contributes immensely, and if we reject it despite the evidence supporting its safety, we’ll be producing food less efficiently to feed a growing population; we’ll be using more pesticides; we’ll be using more water; we’ll be making farming a less desirable profession at a time where we desperately need more farmers; we’ll be foregoing major nutritional improvements from more vitamins to less trans-fat; we’ll be plowing more, often resulting in greater CO2 emissions; and we’ll have more food shortages brought on by pest and disease outbreaks. Where is the real risk?

Putting it together

There is a big knowledge gap in conversations about biotechnology. In fact, in a 2013 Rutgers survey, folks who described themselves as knowing “very little” or “nothing at all” about GE foods still report having an opinion about the technology. Half of those surveyed said the basis for their opinions was “a general feeling” (versus any specific issues). Given all the intuition factors identified by Stefaan Blancke and his team, and additional psychology well-explored by David Ropeik, it makes sense that the negative perceptions about biotechnology have spread—but that doesn’t make them accurate. What do we do about it?

Let’s start by holding ourselves to a high standard. Let’s check our own intuition against what we know is credible science. And then, let’s apply that standard in all our conversations. It’s too important to let psychological idiosyncrasies rule the day.

This article was written by Liz Caselli-Mechael, MS and reviewed by Tamika Sims, PhD.

Related Resources:

The Tweeters of Doom: How Social Media Impact Food Safety and Risk Communication – Part I and Part II